Chasing the Last Butterfly: Indigenous Knowledge and the Future of Sustainable Cities in Nigeria

Author: Abdulazeez Shomade

Introduction

I was seven when I first saw a butterfly flap its wings right in front of my eyes. I ran after it with awestruck devotion, leaping with extended arms and open palms. I caught air.

My family had just moved from Agege, an energetic town in Lagos, Nigeria, characterized by honks and haste, to a leafy rural community in Ota, Ogun State. Here, the day carried a quiet calm, a silence that was both pleasing and unsettling to someone coming from a bustling urban area.

Credit: via Google

Everywhere, mango and orange trees, wildflowers, medicinal leaves. Far fewer people, diverse birds that I couldn't name, fewer cars, more space. It was as if life exhaled differently here. Then, slowly, something shifted. One building rose, then another. The trees, bush rats and grasscutters, vanished. And where were my butterflies? By the time I was 23, most of the roads were tarred. The living hush became the sound of something receding. I didn’t have the language then, but now I know. What I witnessed was the slow violence of urban expansion.

Credit: via Google

Urban Expansion and the Shifting Baseline

Nigeria’s rapid urbanization has risen sharply, from 15.4% in 1960 to over 55.6% in 2022. By 2050, 70% of the population is projected to live in cities. This growth ushers in new malls, new jobs and roads, celebrated as “development.” But in lived experience, it means forests are cleared for bricks, farmlands erased for asphalt, and indigenous knowledge systems buried beneath the sound of engines.

Essentially, urbanization doesn’t just change landscapes; it alters cultural memory. Each generation perceives a more degraded environment as “normal,” because they lack knowledge of its past, healthier condition: a phenomenon environmental scientists call Shifting Baseline Syndrome. The elders in Ota remember antelopes. I remember bush rats and butterflies. The children there now will remember none of that. To them, concrete and the occasional houseplant feel like nature.

This “forgetting” has consequences for climate action (SDG 13), life on land (SDG 15), and sustainable cities (SDG 11). As urban areas grow, so does energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, increasing vulnerability to heatwaves, drought, and crop failures. And yet, urbanization has erased the very indigenous knowledge needed for solutions: knowledge embedded in traditions intrinsically tied to the land.

Credit: via Google

Before Conservation Was a Policy, It Was Culture.

Earlier this year, on a research trip to Ajura village in Ogun State, I walked through a community that reminded me of home before the buildings. The greenery was still dense and one could feel the shawling embrace of nearby streams. I was there to talk to hunters, but what I found was a living archive, a sophisticated system of indigenous environmental governance where cultural rules function as conservation law, threatened by economic development.

The foundation of this system is a unique ecological ethos. The Yoruba see themselves as tenants on God's Earth, coexisting with other beings, including animals, plants, and even geographic features like hills and forests. This holistic worldview frames the environment as a sacred creation. As decolonial scholars like John S. Mbiti argue, the African worldview is inherently religious, informing conservation practices where respect is maintained through taboos. This explains the existence of sacred groves, places where the fear of spiritual consequence enforces a powerful fence around biodiversity.

Credit: via Google

This worldview translates into concrete, ethical rules. The hunters' relations with animals, around whom their occupation revolves, are governed by a complex ethical code. As the hunters narrated, some animals are spared at certain times or for various reasons. For instance, vultures and ground hornbills are revered and forbidden from being killed. Likewise, hunters are forbidden from killing animals while they’re mating, a restriction born from a ‘moral concern’ that acknowledges animals feel pain and pleasure like humans. This functions as a vital mechanism for conserving wildlife and ensuring population growth.

Credit: via Google

Credit: via Google

These ethical principles are embedded and enforced through rich cultural expressions like proverbs, storytelling, taboos and totems. Technically, totemism is a form of social identity where a clan associates itself with a non-human animal. Seen as a spiritual link to the divine, the clan regards it as its totem and forbids its abuse. For instance, certain families in Yorubaland prohibit the killing of parrots and buffalo because they are spirit animals. Similarly, some Igbo tribes in South-East Nigeria revere certain snakes, making them de facto protected species. What remains fascinating is how `oríkì` (praise poetry) for animals, proverbs and folktales constructed from the observation of animals, has woven conservation into the very fabric of cultural heritage to ensure intergenerational knowledge is preserved.

Credit: via Google

Crucially, these traditional systems demonstrate a prescient alignment with modern science. The Yoruba taboo against killing vultures, viewed as an abomination, is ecologically vital. Vultures control disease transmission and recycle nutrients, their unique immune systems preventing the spread of zoonotic diseases. This synergy between cultural belief and ecological function shows that indigenous knowledge systems functioned as environmental regulation long before modern conservation laws existed.

Spiritually-governed forests and rivers are today governed by state-sanctioned regulations on reserved forests, indicating beneficial state-backing of traditional practices. However, this living archive exists in a precarious state. Specifically, while hunters still preserve trees based on the worship of Ogun (the Yoruba god of iron, war and technology) and enforce community rules in publicly accessible forests, the very knowledge that has sustained their livelihood for generations is eroding. The growing blind acceptance of Western scientism - the hegemonic attitude that positions it as the only valid knowledge - and pressing economic needs which force communities to sell their lands to industries and modern builders, challenge the continuity of these practices.

Colonial Legacies and the Politics of Knowledge

It is important to point out here that the emerging change in Ajura village is built on a colonial inheritance. Western planning models positioned the city as the sole symbol of modernity and relegated rural ways of life as backward. This ideology systematically dismissed traditional conservation as unscientific. When colonial administrations imposed Western-style conservation—fences, permits, and remote bureaucracy—they deliberately dismembered organic, community-owned governance systems. This is why urban areas in Nigeria often rely exclusively on Western science for resource management and environmental crises management.

This epistemic injustice persists today as institutions in the Global North often mine indigenous knowledge for baseline data while overlooking its sociocultural foundations. This extractive approach treats Indigenous Knowledge (IK) as a resource to be validated by Western science, rather than as a valid, systematic knowledge system in its own right. This is cognitive injustice, rendering the preservation and restoration of this body of indigenous knowledge, a cultural, political and ecological imperative.

Achieving the SDGs through IKS

To achieve the SDGs, Africa must recognize Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS) as critical resource management system. The path forward requires three paradigm shifts:

- Epistemic humility and Co-creation: Policymakers and scientists must acknowledge that Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is science built from age-long observation and adaptation. Thus, the goal is to create dialogical spaces where scientists, policymakers, and knowledge-holders meet as equals to design hybrid solutions: urban planners and hunters/farmers could unite to co-design a city's green belt.

- Legal and Policy Integration: We must integrate IKS principles like totemic protection and hunting taboos into national biodiversity strategies, empowering community-based resource management within urban planning frameworks. While full legal and policy integration may be gradual, incremental adoption through pilot projects, local bylaws, or community-driven biodiversity initiatives is both realistic and impactful. Integrating totemic protection and hunting taboos in this way directly advances SDG 15 (Life on Land) by protecting biodiversity and lays the foundation for SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) by embedding ecological wisdom into urban growth.

- Intergenerational Transmission: It is critical to support communities in the documentation of their knowledge and in revitalizing the social and spiritual institutions through which Indigenous Knowledge (IK) is traditionally transmitted. Embedding local environmental ethics into school curricula will foster the responsible consumption patterns required by SDG 12 (Responsible Production & Consumption).

Credit: via Google

This blueprint extends beyond Nigeria, offering a model for other African nations where Indigenous Knowledge Systems continue to guide sustainable land use and conservation practices. Time-tested local customs such as community forest taboos, rotational farming, and water-conservation rituals, offer scalable models for planetary health by preserving carbon-rich forests and strengthening ecological resilience in line with SDG 13 (Climate Action).

Credit: via Google

Conclusion

Urbanization is not evil. Given the march and globalizing directions of history, it is almost inevitable. But when urbanization becomes a blind march that erases everything that rooted us, it becomes a wound dressed as progress. The future we imagine cannot survive on concrete alone. It needs memory. It needs the knowledge of the hunters who spare the mating animal, the grandmothers and traditional medical practitioners who know the medicinal leaves, and the communities that see the environment as a sacred relative.

This knowledge, forged and passed down over centuries, is almost visceral. It is also our most sophisticated tool for building cities that breathe, economies that nurture, and an environment that thrives. When the last butterfly disappears, it won’t just be an ecological loss. Memories will have been lost. Then, it becomes easier to believe there is nothing left to save. Integrating Indigenous Knowledge is how we remember the way back to a living world, and in doing so, how we save ourselves.

Bibliography

Mbiti, John S. African Religions and Philosophy. Heinemann, 1969.

Pauly, Daniel. “Anecdotes and the Shifting Baseline Syndrome of Fisheries.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution, vol. 10, no. 10, 1995, p. 430.

Olupona, Jacob K. African Spirituality: Forms, Meanings and Expressions. World Wisdom, 2000.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). “Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities.” United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal11"

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). “Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production.” United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal12

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). “Goal 13: Climate Action.” United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal13

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). “Goal 15: Life on Land.” United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal15

UN-Habitat. Nigeria Country Brief. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), 2023, p. 2. Available at: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2023/07/nigeria_country_brief_final_en.pdf

UN-Habitat. Nigeria Country Brief. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), 2023. Available at: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2023/07/nigeria_country_brief_final_en.pdf

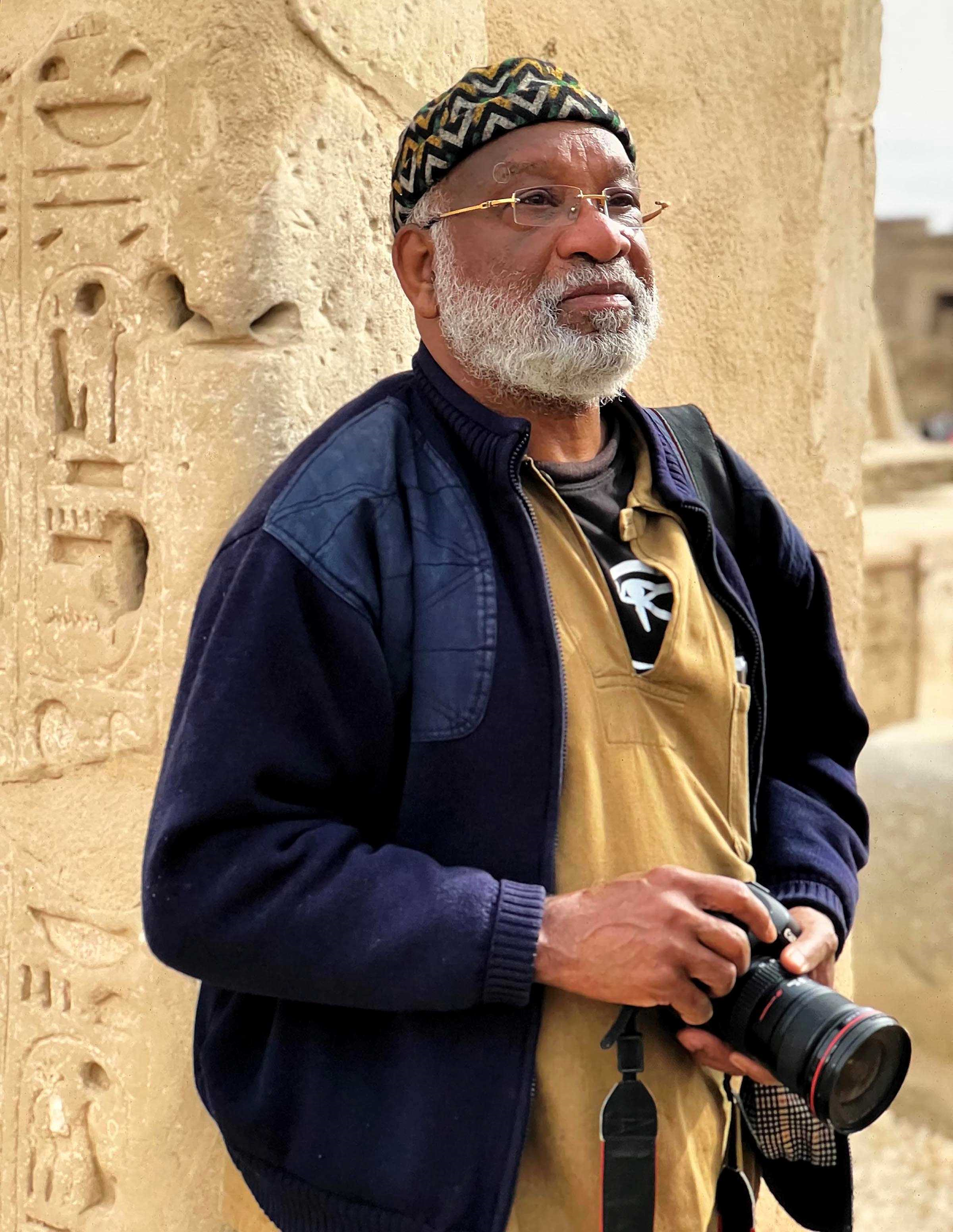

Career Profile – Abdulazeez Shomade

Abdulazeez Shomade is a Nigerian writer and researcher whose work sits at the intersection of climate, culture, and society. He holds a B.A. in History and International Studies from Lagos State University and an M.Sc. in International Relations from the University of Ibadan, where he is currently an MPhil/PhD researcher at the Centre for Sustainable Development, focusing on climate and society in Nigeria. Over the years, Abdulazeez has worked across research, marketing, and advocacy, crafting strategic communication for brands and development-focused initiatives. His writing, which spans fiction, poetry, and nonfiction (including eco-poetry), has been published in journals and anthologies across Africa, Asia, Europe, and America. Passionate about decolonial environmental thought, climate justice, human security, and critical international relations, he blends ethnographic research with creative nonfiction to bridge knowledge systems and influence policy discourse. His work explores how climate action, gender equality, and institutional collaborations, both governmental and non-governmental and across the Global North and Global South, can drive sustainable development in West Africa.

Author: Abdulazeez Shomade

About the African Perspectives Series

TheAfrican Perspective Series was launched at the 2022 Nigeria International Book Fair with the first set of commissioned papers written and presented by authors of the UN SDG Book Club African Chapter. The objective of African Perspectives is to have African authors contribute to the global conversation around development challenges afflicting the African continent and to publish these important papers on Borders Literature for all Nations, in the SDG Book Club Africa blog hosted in Stories at UN Namibia, on pan-African.net and other suitable platforms. In this way, our authors' ideas about the way forward for African development, can reach the widest possible interested audience. The African Perspectives Series is an initiative and property of Borders Literature for all Nations.

Copyright Statement

First published on Borders Literature for All Nations (www.bordersliteratureonline.net) as part of the African Perspectives Series.

Borders Literature for All Nations is registered with the Nigerian Copyright Commission (NCC). Registration No. LW0620.

All rights reserved. Please credit the author and site when sharing excerpts.

For permissions, contact: info@bordersliteratureonline.net cc: bordersprimer@gmail.com

Updated and re-illustrated edition prepared for the anthology Living Sustainably Here: African Perspectives on the SDGs (2026).

© 2026, Selina Publications, (A division of Selina Ventures Limited)

Selina House, 4 Idowu Martins Street, Victoria Island, Lagos, Nigeria

Email: selinaventures2013@yahoo.com